It started with a friend mentioning it would be fun to run draft tournaments online. MTG Arena doesn't support private tournaments—you can play against each other, but organizing an actual draft pod with friends and running a bracket? Not happening.

So I figured: how hard could it be?

Around the same time, I'd been curious how well AI coding agents actually perform on complex projects. Claude Code had been getting a lot of praise, and this seemed like the perfect test case. Magic: The Gathering has over 28,000 unique cards, each able to interact with every other in ways the designers never anticipated. The comprehensive rules document is over 200 pages long.

I sat down and estimated the effort. Without AI assistance, building a complete platform—SDK, card sets, rules engine, game server, web frontend, deployment pipeline—would easily be a 6-month hobby project. Probably more, given the notorious complexity of MTG's rules. The layer system alone could eat a month.

A week and a half later, I had a working solution.

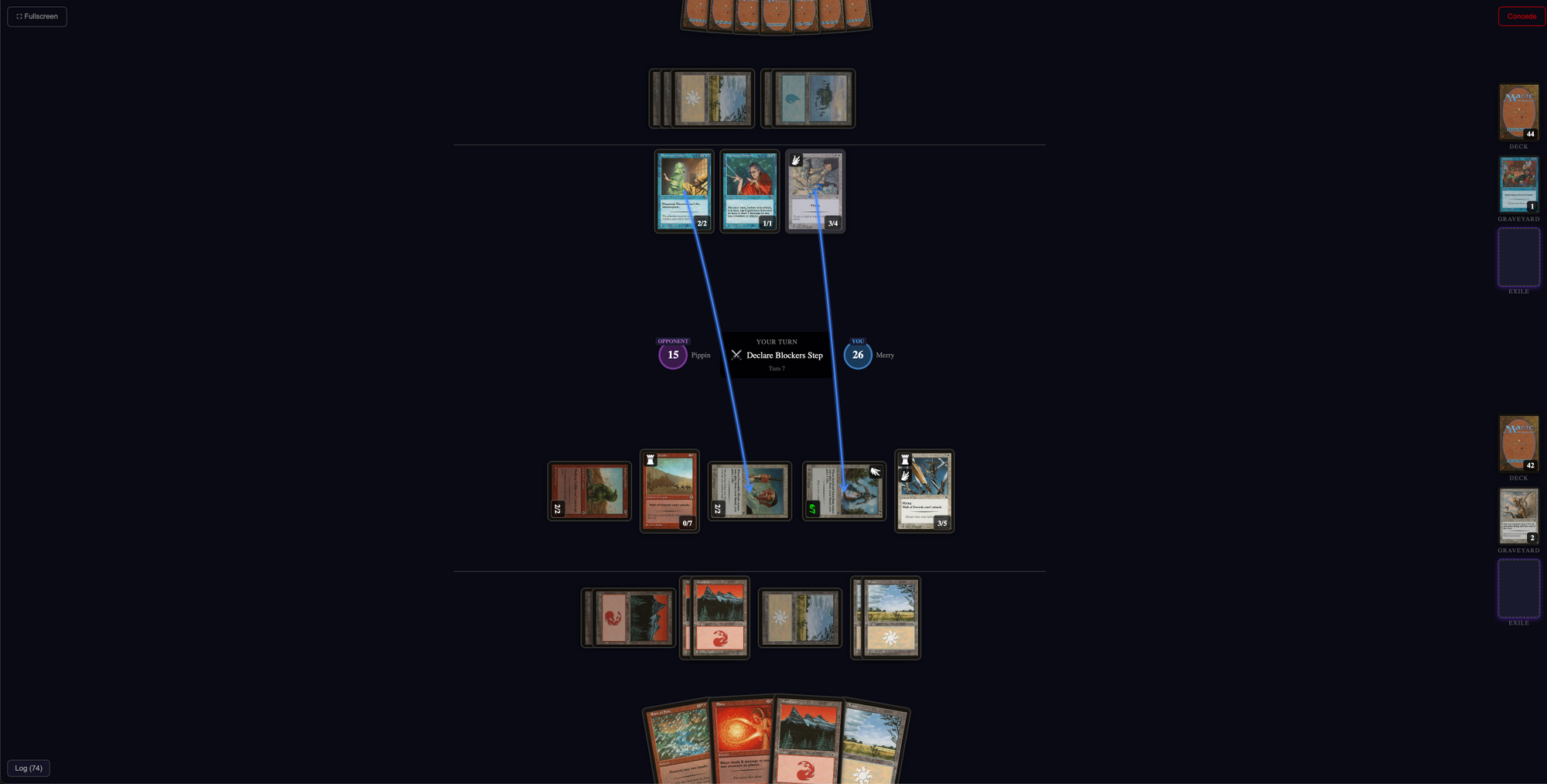

41,000 lines of Kotlin. 12,000 lines of TypeScript. A functional draft system. Real-time multiplayer. And it plays Magic—correctly. The layer system handles Humility. Triggered abilities stack in APNAP order. State-based actions cascade properly.

This was the moment it really hit me how fast this technology is moving.

What Vibe Coding Actually Looks Like

I barely wrote any code myself. Instead, I guided the process—describing what I wanted, reviewing what came back, course-correcting when the implementation drifted. Think of it as pair programming where your partner types 50x faster than you but needs you to keep the big picture in focus.

To keep Claude aligned with my vision, I set up a docs folder containing guidance on architecture decisions, coding style, and design principles. From these docs, I generated a CLAUDE.md file—a dedicated instruction set that Claude Code reads automatically—and kept it up-to-date as the project evolved. This upfront investment paid off continuously: Claude would follow established patterns without me having to repeat myself.

What I loved most was plan mode. Before Claude starts building anything significant, it asks clarifying questions: "How should this interact with existing triggers? Should the effect be optional? What happens if there are no valid targets?" Then it forms a concrete plan and waits for approval. This back-and-forth is invaluable. Half the bugs in software come from misunderstood requirements—plan mode surfaces those misunderstandings before any code gets written.

For architecture reviews, I'd occasionally pull in Gemini. With its million-token context window, I could dump the entire codebase into a single request and ask "does this structure make sense?" or "what am I missing?" The combination works well: Claude Code for the building, Gemini for the birds-eye sanity checks.

The result is a codebase I understand deeply—because I co-designed it—but didn't have to type out line by line. Would I have finished this project without AI assistance? Probably not. It would have joined the graveyard of ambitious side projects that never quite made it.

The Problem

The intuiting might be to take the obvious approach: model cards as class hierarchies. A Creature extends Permanent, which extends Card. Simple, intuitive, wrong.

The problem is that in Magic, a card's identity is fluid. That creature you control? An opponent can steal it. That instant in your hand? It might be a creature on the battlefield (thanks, Zoetic Cavern). That 2/2 bear? With the right enchantments, it's now a 7/7 flying artifact creature with lifelink.

Object-oriented inheritance can't handle this. You can't re-parent an object at runtime. So most engines end up with sprawling conditional logic, special cases, and inevitable bugs when two obscure cards interact in ways nobody tested.

Starting Simple

I started with Portal, the simplified beginner set from 1997. No instants (well a few, but they weren't called instants yet), few activated abilities, mostly just creatures and sorceries. A manageable scope to get the core engine working before tackling the full comprehensive rules.

There's something fitting about that. Portal was how I started playing Magic when I was 8 years old. Now, decades later, it became the foundation for building an engine that handles the full complexity of the game.

Once Portal worked—creatures attacking, sorceries resolving, life totals tracking—the architecture proved solid enough to layer on the rest. The stack. Triggered abilities. Replacement effects. The infamous layer system.

The Full Stack

The project splits into cleanly separated modules, each with a single responsibility:

The SDK

The SDK defines the vocabulary—what a card is, what effects exist, what costs mean. It's pure data structures and a DSL for defining cards. No game logic, no dependencies.

Think of it as the shared language that card definitions and the engine both speak. It provides the building blocks: mana costs, target filters, effect types, duration modifiers:

// The Effects facade - card definitions compose these primitives

Effects.DealDamage(3) // Bolt something

Effects.DrawCards(2) // Blue's favorite

Effects.GainLife(5) // White's thing

Effects.Destroy(EffectTarget.AnyTarget) // Removal

Effects.ReturnToHand(target) // Bounce

Effects.ModifyStats(4, 4, Duration.EndOfTurn) // Pump spell

The SDK is deliberately minimal. It describes the "what" without the "how". A card has a mana cost, a type line, and abilities. An effect has a target and a duration. That's it. The actual game logic lives elsewhere.

The Card Sets

The card sets use that DSL to define actual cards. Portal, Alpha, custom sets—they're all just data. Each card is a declarative description of what it does:

val MonstrousGrowth = card("Monstrous Growth") {

manaCost = "{1}{G}"

typeLine = "Sorcery"

spell {

target = TargetCreature(filter = CreatureTargetFilter.Any)

effect = ModifyStatsEffect(

powerModifier = 4,

toughnessModifier = 4,

target = EffectTarget.ContextTarget(0)

)

}

}

Triggered abilities work the same way:

val ManOWar = card("Man-o'-War") {

manaCost = "{2}{U}"

typeLine = "Creature — Jellyfish"

power = 2

toughness = 2

triggeredAbility {

trigger = OnEnterBattlefield()

target = TargetCreature()

effect = ReturnToHandEffect(EffectTarget.ContextTarget(0))

}

}

Traditional engines hardcode card logic. Want to add a new card? Write a new class, handle all its edge cases, hope you didn't break something else.

Argentum treats cards as pure data. The engine doesn't know about Monstrous Growth specifically. It knows how to create continuous effects. It knows how to handle targets. The card definition just connects these primitives. Adding new cards rarely requires engine changes.

Adding a new set means writing card definitions, nothing more. The sets don't know how the game works; they just describe what cards do.

The Rules Engine

The rules engine is the brain. Pure Kotlin, zero server dependencies. This is where the comprehensive rules live: the stack, priority system, combat phases, triggered abilities, state-based actions, replacement effects, and the layer system.

Entity-Component-System Architecture

Instead of class hierarchies, Argentum uses pure ECS. Everything is an entity—just a unique ID. Cards, players, spells on the stack, even continuous effects like "Giant Growth gave this +3/+3 until end of turn." All entities.

Each entity is defined by its components: pure data bags with no behavior. A creature on the battlefield might have components marking it as tapped, tracking its controller, counting its +1/+1 counters. The entity doesn't "know" it's tapped. It simply has—or doesn't have—that data attached.

All logic lives in systems. The action processor takes a game state and an action, then returns a new state plus events:

(GameState, GameAction) → ExecutionResult(GameState, List<GameEvent>)

The state is immutable. Every game action creates a fresh snapshot, which makes replay, undo, and network sync trivial. Completely deterministic: two identical inputs always produce identical outputs.

The Layer System

Here's where it gets interesting. When multiple effects modify a permanent, they apply in a specific order across seven layers:

- Copy effects (Clone becomes a copy of target creature)

- Control-changing effects (Mind Control steals a creature)

- Text-changing effects (Magical Hack changes "swamp" to "island")

- Type-changing effects (Blood Moon makes nonbasic lands Mountains)

- Color-changing effects (Painter's Servant makes everything blue)

- Ability-adding/removing effects (Glorious Anthem gives creatures +1/+1)

- Power/toughness effects (with five sublayers: setting, modifying, counters, switching)

Get the order wrong and your engine produces incorrect game states.

Argentum separates "base state" from "projected state." The base state is what's stored—the permanent as it exists without modifications. The state projector calculates what players actually see by applying all active continuous effects in the correct layer order.

This separation is crucial. When an effect ends (Giant Growth wears off at end of turn), you don't need to "undo" anything—just remove the effect from the list and recalculate. The base state never changed.

The tricky part is dependencies. Sometimes effect A changes whether effect B applies, which might change whether effect A applies. Consider Humility (makes all creatures 1/1 with no abilities) and Opalescence (makes enchantments into creatures). If Humility is an enchantment... does it affect itself?

Argentum handles this with a trial application system—apply effects tentatively, detect when one effect's outcome depends on another's application, establish the dependency order, then apply for real. It's the kind of edge case that breaks most MTG engines. Argentum handles it correctly.

Because the engine is completely deterministic and has no I/O, testing is straightforward. Feed it a state and an action, verify the output. No mocking, no flakiness.

The Game Server

The game server wraps the engine for online play. It handles WebSocket connections, manages concurrent game sessions, authenticates players via JWT, and—critically—filters hidden information.

The engine produces a complete game state including everyone's hands and library order. The server ensures each player only sees what they're entitled to see:

private fun isZoneVisibleTo(zoneKey: ZoneKey, viewingPlayerId: EntityId): Boolean {

return when (zoneKey.zoneType) {

ZoneType.LIBRARY -> false // Hidden from everyone

ZoneType.HAND -> zoneKey.ownerId == viewingPlayerId // Only owner sees

ZoneType.BATTLEFIELD,

ZoneType.GRAVEYARD,

ZoneType.STACK,

ZoneType.EXILE -> true // Public zones

}

}

Your opponent's hand stays hidden. Scry effects only reveal cards to the player who scryed. The engine can stay pure while the server handles the messy real-world concerns.

The server module also houses scenario tests—integration tests that simulate actual gameplay with player inputs and outputs. These tests verify that cards interact correctly in realistic situations: casting spells, responding to triggers, making decisions. When a new card is added, a scenario test ensures it behaves correctly in context, not just in isolation.

The Web Client

The web client follows what we call the "dumb terminal" pattern. It renders the game state it receives. It captures user intent through clicks. That's it.

submitAction: (action) => {

ws?.send(createSubmitActionMessage(action))

set({ selectedCardId: null, targetingState: null })

}

When you tap a creature, the client doesn't validate whether it's summoning sick or whether you control it—it just sends "player wants to tap this entity" to the server. The server checks legality using the engine, updates state, broadcasts the result.

This eliminates an entire class of bugs where client and server disagree about game rules. If the rules change, you only update the engine. The client stays blissfully ignorant, just visualizing state and forwarding actions.

Each layer stays focused. The engine doesn't know about networking. The server doesn't know about React. The client doesn't know the rules.

Why Build This?

Because I like challenges and I like playing Magic. The comprehensive rules are a 30-year accretion of edge cases that somehow still form a coherent system—exactly the kind of puzzle I can't resist.

Without AI assistance, this would have stayed on my "someday" list forever. Instead, it's live. The layer system handles Humility correctly. Triggered abilities fire in the right order. You can actually draft with friends.

The engine is open source at github.com/wingedsheep/argentum-engine. Play at magic.wingedsheep.com.

— Vincent